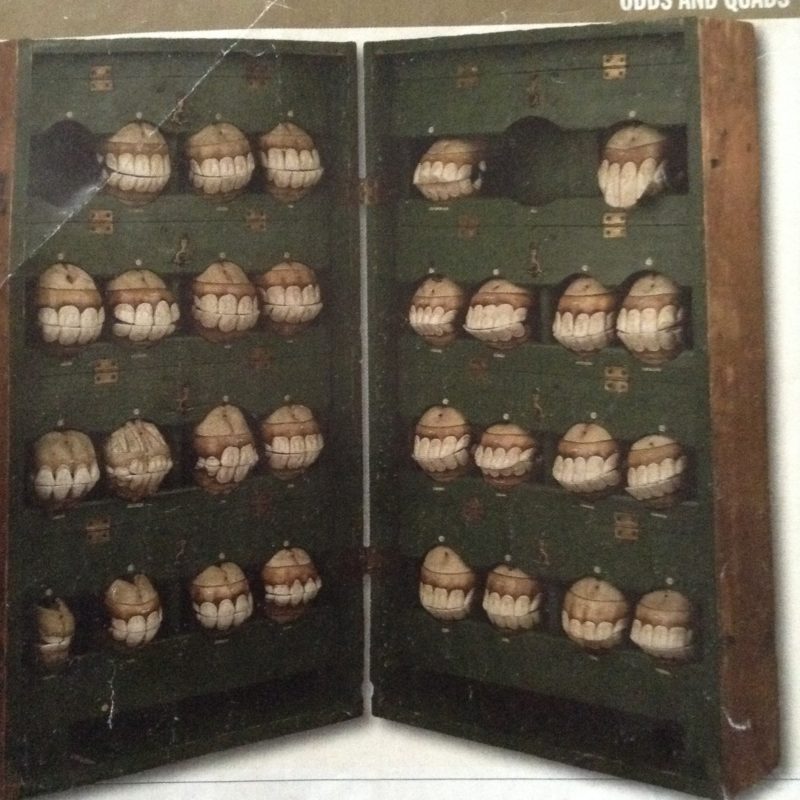

Horse teeth.

That is how I came upon Doctor Louis Auzoux.

His horse teeth collection. Take a close look.

These teeth are made of paper. I fell in love with Dr. Auzoux right then and there. Dr. Auzoux is one man I would like to meet through time travel. How he constructed with a secret recipe of paper mache, cork, clay, glue and love. Passion and love for anatomy and the corpus of human and animal and plant!

Dr. Louis Thomas Jerome Auzoux, a medical student in 1800s France, began experimenting with paper mache in order to create anatomical models as his frustration with the lack of a real body to study the anatomy had begun to get to him. He called them “Anatomie Clastique”, made of hardened paper paste and whose parts could be taken apart and reassembled.

By 1828, he had 100 employees and it seemed this business was flying high and his models were needed, requested and going strong.

These were educational tools and yes they are playful, but I look at them as art pieces. Look closer and deeper and one will find more than a “model, but one can possibly see the man, the time, the era and more. They are so aesthetically curious and confrontational. Personally, I find them thrilling and compelling.

Look at the drone. Take a close look. Does this really look like paper?

In Berlin, you will find a beautiful fold-out advertisement for this Drone. Looking inside this extensive catalog you will find “Zoologische Lehrsammlung”. Describing the collection of models, wet and dry preparations, etc. If you go to the website you will see the drone, shown here. I emailed the guy in charge many many times. No response. So, I showed up at the stunning ancient building on the Humboldt campus in Mitte, that looks like some idyllic countryside picnic sight. Just stunning.

I discovered a gorgeous glass cabinet, that contained some amazing glass pieces. But the drone was nowhere to be found.

I ended up being introduced to the head of the collection, who was busy teaching and I apologized profusely, but I had emailed him many time and thought I would just “stop by”. He was not happy. In fact after asking him a few questions, I sensed he was outraged that I had “just showed up” and not even called. Hello Deutschland!! Not good!! Big mistake! Well, I said to him that the brochure seems to advertise the collection and that I had no idea this was a big secret. He told me that he didn’t want to advertise and didn’t even address the catalog. Maybe he didn’t know that his University was doing the branding with this drone and other precious pieces in the collection?

(Footnote: I began writing this blog way back in 2015/2016, and since I wrote this, the website no longer shows the Drone. The drone is DEFINATELY missing from the brochure. I think they caught on. Maybe after I just “popped by” they were so outraged and fearful that they took the drone off the website!)

He was kind enough to allow me to take some photos of other objects that I ended up doing another post on, but he would not show me the eponymous drone. No way!

So you’ll have to do with the image.

I hate using this forum to complain, but why do famous universities place this fine image on their website, “advertising”, no less print out a super expensive catalogue of “Die Sammlungen der Humboldt- Universitat” publicizing, expounding, showing off no less their “30,000 objekte umfassenden heute noch intensive” (“30,000 incredible objects”!) And then snub you when you simply ask to take a 5 min glance! I don’t get it? So then why grandstand this, when it is such a secret?

I know, I know “what a complainer”. Am I a “Down Dora?” Nope, I just don’t like these contradictions. But contradictions are the way of this life! I still fight it! And the gentleman professor was extremely dismissive like he wanted me out out out. (He claimed he was fearful that people would come in and steal the objects.) I thought to myself: “Ah, most are locked up in ancient glass cases, no less the DRONE is shrouded in LA COSA NOSTRA mode of silence and solitude probably held in a million dollar safe underground!”

So I took my next move to find an expert on these items. And someone who wasn’t trying to shield me away from the object! And you certainly couldn’t find an “expert” at the HUMBOLDT so I found her in London. I was fortunate enough to speak to one of the foremost historians on the subject, Dr. Anna Maerker who teaches in London. Please have a listen and check the podcast below and I will calm down.

Outrage is my middle name!!

Dr. Auzoux began his experimentation with anatomical models while finding inspiration from Dr. Jean-Francois Ameline, Prof. of Anatomy at Caen whose mannequins were part real skeleton, but cardboard was fixed to the real skeleton. These pieces could all be dismantled layer by layer, showing nerves and vessels. Dr. Auzoux began to explore his own method by using artificial bone and doing away with anything “real”. And this is where the dazzle began! He was able to produce these industrial type models, with an affordable price and find a vast distribution all geared to teaching future animal doctors, horse breeders, and general learning about the body and anatomy from insects to mushrooms to snails.

At first, he created a female human model, with all the organs, calling it “clastic anatomy” from the Greek “klaein: to break up or separate” describing the educational dismantling.

He began to work with fish, turkey, insects like leeches and even reptiles as models. Particular animals to the economy at that time were bees, silk worms because of the textile industry and followed by horses as they were of major important day to day and also for the military cavalry. In the field of agriculture and breeding, these areas were of interest to him. The whole process of formulating the model of the horse was exceptionally daunting.

I recommend reading the incredible article by Christophe Degueurce and Philip J. Adds from St. George’s University of London. This article will describe the intricate process of envisioning the various life-size models of various types of horses and their ailments and issues. I have also taken some information from these papers, so much credit to the article.

Along with the body, he created a series of pathological equine legs, with various issues that were common in that age, such as lesions. During this time he produced the first image we see in this post, of the horse jaws. This was around 1850 and each jaw would correspond to the animal’s age. The importance of understanding the age of the horse was a vital skill for the cavalry officers who were required to procure horses for the army. Overall, Auzoux felt he could contribute to greater horse breeding, no less help overcome problems with hygiene along with the health issues having to do with horses, sheep and other animals. But it seemed his main focus and challenge was the horse, as the number of models he created is truly astounding. His horse models can be found all over the world, from India to Australia. The issue now is how to preserve and care for these incredible life-size pieces as they slowly deteriorate and decay.

I cannot stress how intricate these objects are. When you have the privilege of looking at the real thing (the REAL Dr. Auzoux anatomical objects) and like a surprise within each packaged organ, you open and reveal more and more innards of the animal or plant, unveiling each miracle of the body intelligence. Here is a profound example of the silkworm and her subtleties. Thank you Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, Austrailia.

“Anatomical model of a silkworm constructed from papier-mache and painted plaster with connecting metal hooks. The back of the silkworm can be removed to show the internal organs including the thorax, abdomen and intestines, brain and muscle structure on the underside of the back. On the exterior of the silk worm is shown its mandibles and silk producing glands, three pairs of thoracic legs, four pairs of abdominal prolegs and a pair of anal prolegs. Covering the outside of the body are setae (stiff, strong hairs that help the silkworm to attach itself to surfaces without sliding) and fine particles of silk. The model is painted cream with pale blue, brown, pink and green detail, especially on the internal organs.” (Taken from

The secret recipe seems to go like this: “The models are made with a grey paper pulp, containing granular particles and short fibres. Flax is added to the pulp for models of insect parts, veins and nerves. Auzoux used moulds made from plaster and, later, innovative anatomy moulds for the solid parts of the models. Plaster coats the outside for strength and to provide a base for the paint. The paint is protein-based egg tempera and is protected by a layer of Russian fish glue for models made before 1917, and wood varnish for models made afterwards. ”

“A common feature of many of Auzoux’s models is the use of paint on a thin plaster layer which covered the papier-mâché. Studio artists were employed to add the finishing touches using egg tempura which gave a shiny gloss to the finished work. Iron supports were included to reinforce the delicate areas of some models and metal was sometimes used to connect separate parts.”

“This zoological model of a silk worm was manufactured by the firm run by Dr. Louis Auzoux. It is segmented to allow the removal of the exterior to reveal the organs and tissues inside the silkworm and was made between 1865 and 1884. Its exaggerated size allowed students to easily examine tiny details while the painted colours were often closer to life than the specimens preserved in alcohol which tended to lose their colour. Dr. Auzoux’s models were acclaimed throughout Europe and this model was purchased from the German dealer Chrétien Vetter in 1884 some four years after Auzoux had died.

I am hoping with more publicity, and with Dr. Anna’s future book, a curator from maybe THE WELLCOME INSTITUTE would curate a show on DR. AUZOUX and his anatomical work. Not just the horses, but the smaller pieces that can be found in America, Scotland and even in South America. The goal would be to inspire new conservation initiatives for all his pieces around the world, gathering them and displaying this genius and these profound art works that represent a type of thinking, and a way of understanding the body and the world in the mid 1800’s. I call for a conference on Dr. Auzoux!! (Maybe it has happened already? I wonder.)

Research paper: The Mannequins of Dr. Auzoux, An Industrial Success In The Service of Veterinary Medicine.

Dr. Louis Auzoux (1797-1880) is well known for the anatomical models of papier mâché that he produced and exported all over the world. Although the human models are more widely known, they are by no means the only ones that the famous medical industrialist designed and marketed: animals, plants and especially flowers are another facet of his art. Models of the horse were especially important for Auzoux’s business. The paper horses, the sets of bone defects and jaws that he created were purchased in great quantities by the French government of the day to provide the materials needed for training recruits in a time of war. There was also a programme to improve horse breeding throughout France through these fascinating objects. These magnificent creations that were distributed all round the world, and which once were the pride of France, are now damaged, ignored and dispersed. Sadly, they are now in great danger of being lost forever.

French Dr Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux (1797-1880), a pioneer of three-dimensional teaching models. As a medical student, around 1820 Auzoux developed an anatomical model of a life-sized male human. The artificial body was made from a paper paste which could be “dissected” into pieces — the forerunner of today’s classroom models in plastic. This development had important implications for model production, distribution, and use. For the first time, anatomical models could be moulded and produced in series, they became affordable for a wide range of users, and their robust material allowed for hands-on interaction and global travel. The various marketing strategies of the tireless Auzoux made his models a world-wide success. They captured the imagination of diverse audiences in the nineteenth century, and even today, these models could still be found in collections from Cairo to Tokyo. After an initial focus on models of normal human anatomy, Auzoux branched out into the production of models of animals and plants, often at an extremely large scale.

(Taken from Dr. Anna Maerker article: Papier-mâché Botanical Models of Dr Auzoux)

Note: Please again notice the intricate nuance of each piece!! I mean, really? Look at this. It is paper!! To think this was done in the 1800s and now we have digital. But really, who made greater advances in progress? I am down with Auzoux and Co. vs the digital disaster of today. Beam me back there Scotty!!

Listen to the Podcast here: Dr. Anna Maerker from Kings College, Senior Lecturer in History of Medicine.